It’s every collector’s dream to discover a long-lost treasure, especially if it has been hidden away for many decades. Such discoveries often make headlines around the world and not just in the philatelic press. John Wright discusses the stories behind some of the most famous and infamous headline grabbers from over the years.

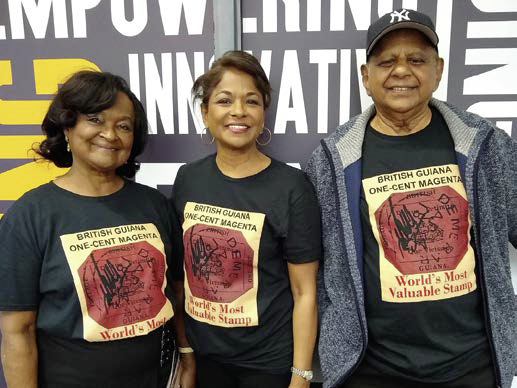

When people start wearing T-shirts with a picture of a stamp on them, you know that something’s up – especially when you see them all smiling! (Fig 1) The British Guiana 1c. Black on Magenta, the world’s most famous and valuable stamp (by being the only one known to exist) (Fig 2), thrilled not just the stamp collecting world but the wider public when it was bought at auction in the USA in June 2021 for a staggering $8.3m (including buyer’s premium). One can only imagine what the person who originally stuck it onto an envelope in 1856 would think about that. The lucky buyer, Stanley Gibbons, not only made it immediately available for viewing at their flagship store at 399 Strand, London, but also still allows any of the rest of us to co-own it. The thrill of something so precious being found always shines a light on the prospect of the next lost stamp turning up, however famous, infamous or, more commonly, with a story but no fanfare. It also makes one hope that the original finders, in this case a child, are treated faithfully. It was 12-year-old Scot Louis Vernon Vaughan, who lived in the Guyanese county of Demerara (whose postmark the stamp bears) and found it in 1873 amongst his uncle’s letters. He sold it to a local collector some weeks later for six shillings. Naturally, whenever such large sums are involved along come the inevitable fakes. Other stamps purporting to be a 1c. Black on Magenta have duly popped up, such as one in 1999, claimed to have been discovered in Bremen, Germany, owned by German ‘stamp reproducer’ Peter Winter – well known for printing famously rare stamps as facsimiles on modern paper – but the stamp was twice-quashed under steely examination by the Royal Philatelic Society London.

Fig 1 Guyana Philatelic Society members with British Guiana 1c. Black on Magenta T-shirts (Image source Philafrenzy, Wikimedia Creative Commons)

Fig 2 The British Guiana 1856 1c. Black

on Magenta stamp, found in Georgetown, Guyana by 12-year-old Louis Vernon Vaughan

The celebrity factor

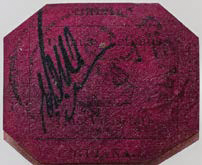

Of course, the word ‘lost’ can be used to imply mystery, evident or not, such as the Mirror’s March 2016 story headed ‘John Lennon’s lost album’ of stamps, which he collected as a child, complete with the future Beatle’s cheeky doodles (Fig 3)’.

Fig 3 The first page and the New Zealand pages from John Lennon’s ‘lost’ childhood stamp album (Image courtesy of the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, USA

Not exactly ‘lost’ at all, the album has the charm of a child’s handwriting at the front where John wrote his name and address and numbers crossed out showing the running total of stamps he had in it, not forgetting the painted blue beards he added to the printed faces of Queen Victoria and King George VI. Sold by Stanley Gibbons to the US National Postal Museum in 2005, reportedly for £29,950, it is valuable simply by being Lennon’s; made even more touching by the fact that in 2018 the US Postal Service issued a John Lennon Forever stamp. Genuinely lost, for 59 years anyway, was a letter (first day cover with a blue fourpenny Jubilee Jamboree stamp) that Boy Scout William Knight sent to himself in 1957 from the 6th World Rover Moot (an event for 18-25-year-olds called Rovers – he was 28) held at Sutton Coldfield, West Midlands. It arrived 20 years after he died at the age of 67. The letter found its way to his sister, Mary Bristow, who told the Daily Express in December 2016 that William ‘had sent the letter to himself so he could get his stamp collecting badge to go on the sleeve of his Scout’s jumper’. Sometimes ‘lost’ means believed lost. A 2010 special philatelic auction at the Rapp auction house in Wil, Switzerland attracted several hundred stamp collectors and investors from all over the world; in it was a collection from Ticino, the southernmost Swiss canton, with a surprise. It contained a cover, previously thought ‘lost’, bearing three copies of the so-called Neuchâtel stamp (Fig 4). Appearing on a cover dated 1 January 1852 and addressed from Geneva (the second of the Swiss cantons to issue postage stamps) to the Canton of Fribourg, this cover was expected to fetch more than 250,000 Swiss Francs (CHF) (or some £263,000 today). In the end the cover sold for CHF 348,000 (including surcharge without VAT), according to Ilona Würgler at Rapp. Disaster mail Of course, the worst way for a stamp or cover to disappear is in an accident. When Queen Victoria was 60 she would have heard the news on 28 December 1879 that a train heading across the River Tay in Scotland (and only minutes from arriving at its intended destination of Dundee on its northern bank) had crashed into the river. She herself had travelled across that very same newly built and presumably sound iron-framed Tay Bridge when she had opened it in June 1878. Yet a Board of Trade inspector four months before (the Report of the Court of Enquiry noted) had made this vague pronouncement: ‘When again visiting the spot I should wish, if possible, to have an opportunity of observing the effects of high wind when a train of carriages is running over the bridge’. No action followed. It would have been packed with passengers full of Christmas spirit when the sixcarriage train approached Dundee in a storm and entered the Tay Bridge at about 7.15 on the evening in question. When it reached the middle of the bridge the structure collapsed and the train dropped into the river, causing the death of every one of the approximately 75 people on board, the Minutes of Evidence noting that divers later found the train ‘still within the girders’. Poignant reminders of that awful incident surface today in the form of the mail carried by that train that was later retrieved from the River Tay. An envelope from one of these letters was a prize exhibit at a stamp auction on 6 February 2012, run by Robert Murray’s Stamp Shop in Edinburgh, and carefully catalogued as follows: ‘1879 cover London to Dundee, probably recovered from the Tay Bridge Disaster… with penny red plate 213 cancelled by London EC duplex mark (DE 27) – stamp has become detached and been replaced in slightly incorrect position… Manuscript note… reads, “In the train that fell with the “Tay Bridge”’ in a style that appears contemporary’. It is known that two bags of mail were washed up from the wreck, with perhaps only about ten items known to have survived. It fetched £880 (Fig 5).

Fig 4 The ‘lost’ Neuchâtel cover, auctioned in 2010 for nearly 290,000 Swiss Francs (Image courtesy of Auction house Rapp, Switzerland)

Fig 5 A letter recovered from the train that fell with the Tay Bridge, Dundee, Scotland in December 1879 (courtesy of Robert Murray’s Stamp Shop, Edinburgh) (Reduced)

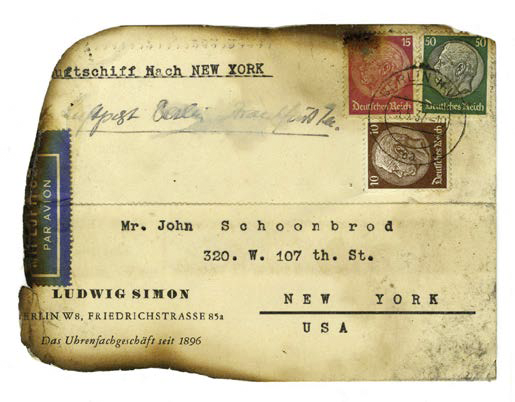

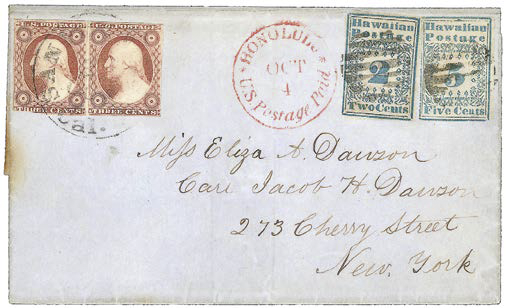

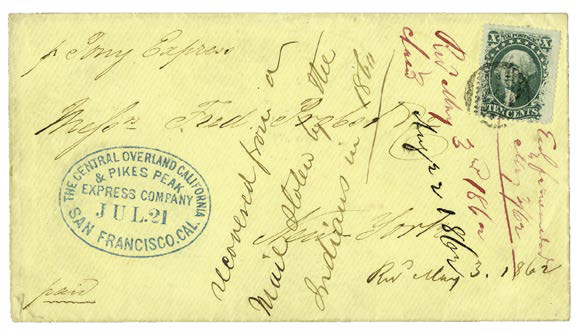

Another envelope, auctioned in London as an item from the Tay Bridge Disaster, had turned up some two years previously under curious circumstances. In a smudged and harder to read blue envelope, the Aberdeen-addressed letter had been posted on 27 December from Forres (both places well north of Dundee) and was possibly sent south with all the Christmas mail, say to the bigger sorting office in Edinburgh, either by mistake or intentionally to be handled more quickly and be re-posted on the illfated north-bound train. This sold for £2300 in 2010, the Grosvenor Philatelic Auctions catalogue noted that the letter had arrived in Aberdeen the day after the disaster. Curious as this sounds, since the train was trapped in the river, it does seem plausible given an odd discovery (although no date or time is mentioned). Word was brought to Mr Gibb, a Dundee postmaster, that several of the mailbags that were on the train were picked up on the beach at Broughty Ferry, on the Tay’s northern shore. From there they were presumably dispatched to finish the rest of their 60-mile-plus journey to Aberdeen. Letters recovered from fire invariably record extraordinary events. The Hindenburg was the German passengercarrying airship that caught fire on 6 May 1937 over New Jersey, USA, killing 35 of the 97 people on board – one cover (among 360 of 17,000 items of mail on board that were recovered) – showing scorch marks is shown at Figure 6. Another rarity rescued from fire was the 1852 ‘Dawson Cover’, the only known cover bearing the Hawaiian 2c. value Missionary stamp. It was rescued from a furnace in 1870 (Fig 7). Sometimes letters simply fall off the back of a horse. America’s most extraordinary and rarest example is an 1860 Pony Express cover, carried via the famous Pony Express service from San Francisco eastward to St Joseph, Missouri – that is until the rider heard the galloping hoofs telling them that American Indians were approaching fast. The Smithsonian National Postal Museum adds the grisly point that, ‘the Pony Express rider was overtaken (and purportedly scalped)’. The horse must have run off with the letter pouch, which was later recovered from the plains, this letter was finally delivered two years later, the message written on the front, ‘recovered from a mail stolen by the Indians in 1860’, providing indisputable evidence of what had happened to it (Fig 8).

Fig 6 A piece of disaster mail recovered from the wreckage of the airship Hindenburg, which caught fire on 6 May 1937. Over 360 of more than 17,000 pieces of mail on board survived (Image courtesy of the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, USA) (Reduced)

Fig 7 The Dawson Cover, 1852, the only known cover bearing the Hawaiian 2c. value Missionary stamp, which was found in a furnace in 1870; a scorch mark is still visible on the cover’s edge (Reduced)

Fig 8 Recovered

from mail stolen by American Indians. A 10c. Washington stamp on Pony Express cover from 1860

(Image courtesy of the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, USA) (Reduced)

A long-lost piece of the jigsaw

It is every stamp collector’s dream to be the one to stumble onto something similarly precious. And so it was in 2020 with Stuart Chandler of Henley-on-Thames-based Empire Philatelists whose find meant the welcoming back a missing piece of history: a long-lost Barbados rarity hiding from him among a batch of Commonwealth stamps he’d acquired. ‘You always think it’s out there somewhere’, Stuart told me. ‘We’re always on the lookout for that elusive discovery. At first I didn’t notice it as there were so many pages, but when I started to break it down I spotted it quite quickly’. He had bought a huge comprehensive collection at Spink’s auction house, a general A-Z Queen Victoria to King George V Empire Collection with a view to breaking it down into lots for other collectors to buy. When he reached the Barbados section he started with early imperforate stamps and not long afterwards reached the rarity. ‘Once I removed it from the page it was clear that it was a Perkins Bacon ‘CANCELLED’ stamp, Stuart said, the 1861 stamp soon afterwards appearing on his website for sale for £7950 (Fig 9). The stamp has also been the subject of a book, Cancelled by Perkins Bacon, written in 1998 by Barbados collector Peter Jaffé who described how Perkins, Bacon & Co (famous as printers of the Penny Black) lost their Crown Agents printing contracts after agreeing to a request from Ormond Hill (nephew of Sir Rowland Hill, Secretary to the Post Office, 1854-64) for some ‘remainder’ stamps. Six ‘obliterated impressions’ were then handed over, but the news caused such public fury that Hill offered to return them so long as he could give away any ‘superfluous’ ones. These Barbados stamps had all been struck with a handstamp, with four bars above and below the word ‘CANCELLED’. The whereabouts of four of them were already known, meaning that Stuart’s find was the fifth of the six, its markings showing precisely how it fitted into the jigsaw (Fig 10).

Fig 9 The Barbados 1861 ½d. deep green, infamously handstamped

‘CANCELLED’ by Perkins & Bacon, discovered by Stuart Chandler of Empire Philatelists in 2020

Fig 10 A reconstruction of the block containing the five known ½d. Barbados’ ‘CANCELLED’ stamps which shows the position of the example discovered by Stuart Chandler. The sixth lost stamp is still to be found

Stolen recovered

Crime accounts for many losses. In 1983 the FBI finally recovered 82 stamps valued

at US$500,000, stolen in 1977 from the New York Public Library one May weekend, when the library was closed. Taken from oak cabinets temptingly located next to the information counter, they included a rare 24-cent ‘Inverted Jenny’ (featuring an image of a Curtiss-Wright JN-4 ‘Jenny’ biplane that was printed upside-down by mistake) airmail stamp and an 1867 30-cent orange stamp on embossed paper, valued at $150,000 each (Fig 11). Such thefts have been frequent enough for the FBI, in 2004, to launch a special Art Crime Team, which has since managed to recover some 2000 items valued at around $150 million. Fort Lauderdale stamp collector Michael Perlman was familiar with Charles J Starnes’s stamp collection with 400 covers which had unique pen marks and imperfections. Spotting some of them on eBay, he tipped off the FBI and after bidding $11,000 – without knowing if he would get his money back or not – travelled to Tampa with an FBI agent. The

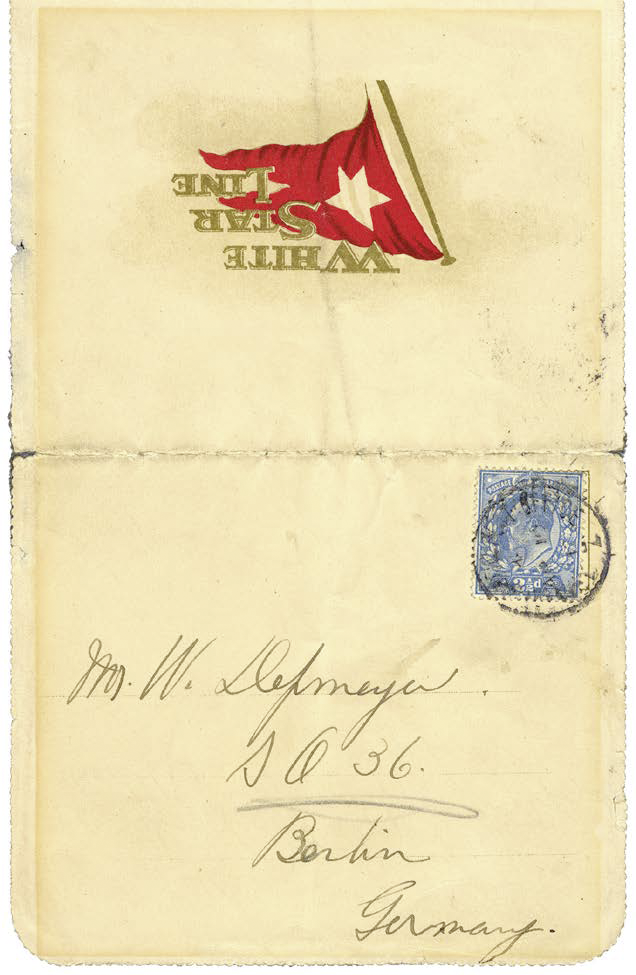

seller didn’t realise they were stolen or were in fact worth about $1 million. Another stamp dealer and his two sons were tied up by thieves dressed as police of cers who came to their Torquay home and stole a £400,000 stamp collection in 2008. Actual police of cers then warned the UK stamp trade about it, one local dealer saying that much of the collection had been photographed and was easily identi ed, making it hard to sell on. Unsung heroes Among all the tales of false hope or mischief in bids to own valuable stamps is the commonplace and usually unsung work of the people who always do their best to look after the mail, however valuable it is. Ironically, there is one example of ordinary stamps and covers becoming priceless – simply by virtue of what was about to happen to them The Titanic is famous for the terrible loss of life involved in its sinking after hitting an iceberg in the Atlantic on 15 April 1912, yet it is not widely realised that its full title RMS Titanic meant that it was a Royal Mail Ship (at the time called a ‘Royal Mail Steamer’) charged with the job of carrying mail under contract with the Royal Mail and US Post Of ce Department. A total of 3364 sacks of mail, some six million items, were being looked after in the Titanic’s Post Of ce and Mail Room deep in the ship on decks F and G (Fig 12). Manned by ve postal clerks (three Americans – John March, Oscar Woody and William Gwinn – and two Britons – Jago Smith and J B Williamson), they worked 13 hours a day, seven days a week and sorted up to 60,000 items a day. Whether they suspected what their ultimate fate might be or not – none of them survived – it does appear to have been a matter of honour for these clerks to keep working. To them it had nothing to do with rarities or famously elusive covers, all of which they would now surely become. It was just the daily duty of care with other people’s property. According to the Postal Museum, when the night-time collision happened the postal workers were celebrating Oscar Woody’s 44th birthday. And when the Mail Room started to ood they set about trying to move 200 sacks of registered mail to the upper decks; even trying to get some stewards to help them, one of whom later said, ‘I urged them to leave their work. They shook their heads and continued at their work. It might have been an inrush of water later that cut off their escape, or it may have been the explosion. I saw

them no more’. A memorial to the ve men would be built in Southampton, from where the Titanic had departed, part of it reading: ‘Steadfast in peril’. All they had cared about was the same as any honest postal worker would think today, getting people’s messages safely to those they had written to. Not that stamp collecting should become too clouded by tragedies since it has always celebrated the whole of human history, not just its happier corners. Variously, seeking rarities can be merely a pragmatic challenge to complete a set, or the simple fun of pursuing the unlikely purely for the sake of it, or an even more earnest wish to feel reunited in some way. For whatever reason we are drawn to this ever-tempting quest, it is certainly the case that whenever some elusive item believed to be well and truly lost does nally turn up it is almost always a show-stopper.

Fig 11 An Inverted Jenny was one of several rarities recovered by the FBI following the theft of stamps valued at US$500,000 from the New York Public Library in 1977

Fig 12 First-class passenger George E Graham, a Canadian returning from a European buying trip for Eaton’s department store, addressed this folded letter on Titanic stationery. Destined for Berlin, the envelope was postmarked on the ship and sent ashore with the mail, probably at Cherbourg, France. The morgue ship Mackay-Bennett recovered Graham’s body. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum, USA’